Good Morning,

Stocks rallied Friday, but still posted their first losing week in six amid heightened inflation fears. The major averages closed the week lower after the hottest inflation report in 30 years. The Dow fell 0.6%, the S&P 500 dipped 0.3% and the Nasdaq Composite inched down about 0.7% on the week.

Consumer sentiment in early November dropped to its lowest level in a decade, the University of Michigan reported Friday. Plunging consumer sentiment prompted hope among traders that the Federal Reserve would delay any interest rate hikes. Many survey respondents cited inflation concerns, according to the report.

Meanwhile, workers left their jobs in record numbers in September with 4.43 million people quitting, the Labor Department reported Friday. The exodus occurred as the U.S. had 10.44 million employment openings that month, according to the report.

Our Take

Inflation is looking a lot less "transitory" after CPI numbers for October showed that consumer prices jumped 6.2% from a year ago, while notching the fifth straight month of a figure higher than 5%. It's also the fastest rate since 1990, and while that might cause some worry in the general population, Wall Street appears to be discounting the effects. Many continue to argue that the Fed won't get too aggressive, inflation could moderate next year, while some think stocks could even benefit along with a rise in asset prices.

Politicians are certainly taking notice: "Inflation hurts Americans pocketbooks, and reversing this trend is a top priority for me. With the [infrastructure] bill we passed last week, and the steps we're taking to reduce bottlenecks at home and abroad, we're set to make significant progress," President Biden said in a statement. "Very soon we're gonna see the supply chain start catching up with demand, so not only will we see more record-breaking job growth, we'll see lower prices, faster deliveries as well. This work is going to be critical as we implement the infrastructure bill and as we continue to build the economy from the bottom up and the middle out by passing the Build Back Better plan."

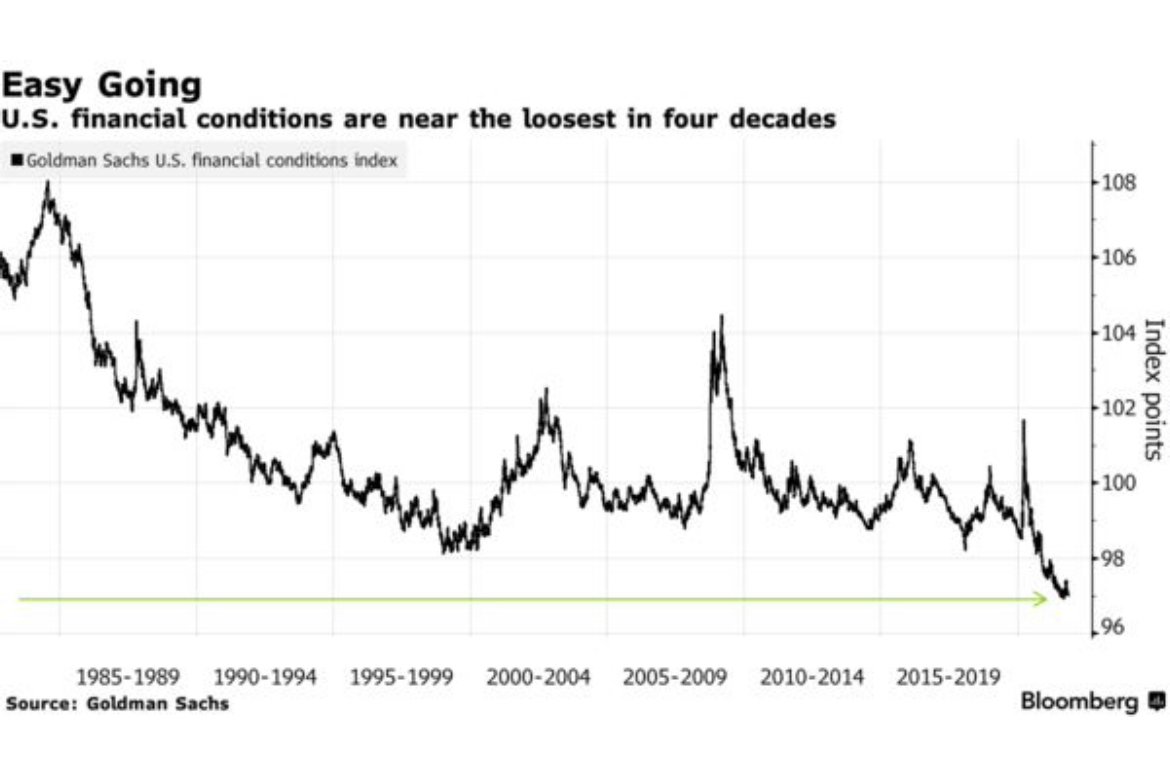

On the other hand, in the face of persistent inflation, central bankers around the world are increasingly looking like they are caught between a rock and a hard place. The only way to keep the economy afloat and the expansion continuing was (and is) to keep rates near zero.

Yet the medicine used to solve the problem of jumpstarting the economy created two new problems: asset bubbles in just about everything, spiralling cost living and an economy that has become addicted to the stimulus drug.

As John De Goey has pointed out, stimulus can be conceptualized as a form of economic antibiotics: antibiotics stop infections caused by bacteria; stimulus stops economic illness caused by slow growth. No one would ever recommend staying on antibiotics indefinitely. Yet given that any change to the status quo risks triggering a financial meltdown, central banks are stuck.

Thus, what appears most likely is that there will be no significant tapering or normalization of any kind until we are faced with the harsh no-win economic ultimatum to do something about inflation that is without a doubt non-transitory.

We haven’t reached that moment yet and there is a compelling argument that we may never reach it as with each passing day the status quo (and associated addiction) becomes more entrenched.

Musings

Observing most of the major indexes, asset classes, economic output and inflation hit record highs, while consumer sentiment hits ten year lows, has prompted us to shift focus away from the “build wealth” side of the coin to the “preserve wealth” side.

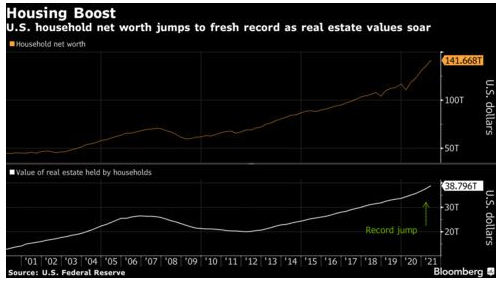

Market participants appear to have discarded caution, worry and fear of loss and instead obsess about the risk of missing opportunity. Worry appears to be in short supply as most investors who have stayed the course over the last decade have done exceedingly well. Despite the fact that about half the U.S. population does not have a significant stake in the stock market, U.S. household net worth has hit record highs led by real estate values and stock prices.

Stocks have surged to record highs, and low borrowing costs have supported a flurry of home buying, and ultimately home price appreciation. Massive support provided by the government and the Fed has bolstered Americans’ wealth.

Gains are so considerable that data suggests they may be fuelling the labor shortage (U.S. workers quitting their jobs just hit record highs) as people exit low-paying work to trade stocks and risky digital assets. Too much money is chasing the risky and the new, driving up asset prices and driving down prospective returns and safety.

What should we make of all of this? In our view what is occurring today appears to be a modern permutation of a classic behaviour. As Mark Twain famously remarked: “History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

Economies, like life, are sine waves with attitudes and behaviour oscillating between peaks and troughs. When it comes to markets, declines can occur because many people’s goal is to become so successful (wealthy) that they can relax (think top of the sine wave), and relaxing leads to complacency (worry is in short supply) which sows the seeds of future decline (and back to the bottom of the sine wave we go).

I’ll always remember a conversation I had with a mentor of mine years ago when he noticed me “over celebrating” a win. He saw celebration as something sloppy, something dangerous, a self-indulgent act that could derail one's focus. He told me “if you have arrived, then what is there left to do?”

Most people’s career goal is to work hard so that one day they can stop working. Our economies are set up around this concept. If we can just get to retirement then we can relax.

The problem is that if enough people adopt this mentality simultaneously and feel that they can“relax”, relaxation is compounded into complacency. Think about the uncertainty and hardship brought on by COVID-19. Perhaps the incredible recent asset price gains and associated investor behaviour can be better understood through this lens.

Becoming financially successful typically requires years of hard, stressful and unglamorous work. It’s understandable that once a certain level of financial success is achieved some feel justified to slow down, kick back, and let their guard down – especially when their assets are rising in value almost daily.

People today understandably need a break from what has been an incredibly taxing and uncertain last two years. Desire for comfort and confidence is high. Bandwidth for skepticism, fear of loss and risk aversion is low.

Investors long for the feeling that they are finally “getting ahead” despite the gravitational pull of inequality/class stagnation and spiralling costs of living. Yet as my mentor so aptly pointed out, there is usually a cost to such indulgence. A cost for casting skepticism aside and replacing reticence with eagerness. Success has an odd way of increasing confidence more than ability. The longer it lasts, and the more it was tied to some degree of luck, the truer that becomes.

Recognizing this pattern and identifying it is key for investment survival as building wealth and preserving it are two different skills.

On the one hand building wealth requires taking risks, being optimistic and swinging the bat. On the other, preserving wealth requires frugality, humility and a healthy dose of skepticism. It also requires an understanding that what you have can be taken away from you just as fast in addition to an acceptance that at least some of what you have can be attributable to luck.

For us, the past two years and the current moment of rapid asset appreciation and high risk tolerance have made us think a lot about longevity and survival. Few gains are worth permanent capital loss and to experience the power of compounding in life and in markets, one must survive the unpredictable dips along the way.

What does thinking about survival and longevity mean for us today in light of the above?

For us it means increasing room for error by focusing on increasing our “margin of safety”. What measures can be taken to raise the odds of success at a given level of risk by increasing our chances of survival:

-Reducing financial leverage

-Flexibility of strategy and worldview

-Increasing willingness to commit capital to investments when risk is obviously being well priced, such as late 2008, 2009 or March 2020 and being less willing when risk is not being as well priced like 1999, 2007 and perhaps today

-Adopting an attitude of patience, humility and skeptical optimism about the future

-Having clarity on one’s investment time horizon

-Focusing on avoidance of accidents and permanent losses - recovering from disaster is difficult if one loses 50% on an ill-considered investment as a 100% gain is needed just to get back to where you started

-Respecting uncertainty by not assuming that the period ahead will resemble the period one most recently experienced

-Avoiding faddish and vogue investments

-Avoiding business models that are particularly vulnerable to technological change as well as those with opaque balance sheets or too much financial leverage

-Focusing on businesses that are less vulnerable to competitive forces - think DHR, WST, MSFT, CRL

With a focus on increasing our “margin of safety” we can increase our odds of hitting the ball out of the park without ever swinging for the fences. During “go go” times like these in which investor behaviour evidences a widespread belief that risk is low, winning becomes about not losing...

Charts of the Month

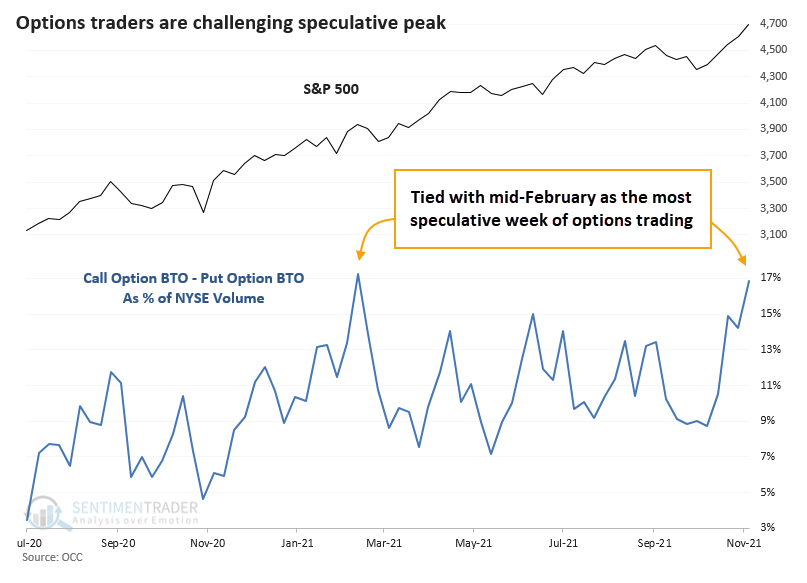

When looking at the sheer volume of money flowing into the market, it's easier to understand today's price action. Whether it's the record flow of speculative options volumes, or the torrential downpour of cash flooding into the broader equity markets, we've simply never seen anything like this:

Traders are nearing the all-time speculative blow-off peak from February, with the smallest of traders spending 53% of their volume on buying calls to open. That ranks as the 4th-most out of the 1,141 weeks since January 2000. It's even more extreme among large traders.

Among all traders on all U.S. exchanges, net speculative volume is equal to the peak during the week ending February 12. There's no point showing the complete history because extremes over the past year are so far beyond anything seen in the prior 20 years that it completely distorts a chart.

Investing capital when prices are exceedingly above the underlying growth trend repeatedly had poor outcomes. Investing money at peak deviations led to very long periods of ZERO returns on capital.

The S&P 500 ended October with a return greater than 20%, and when that's the case the index has never been lower - neither in the month of November, nor in the months of November and December, combined.

Heading into November with the S&P 500 up 20%+ for the year means that the average returns investors may expect are 3.7% for November and 6.2% until year-end. That's significantly higher than the average year's returns of 1.7% and 3.2%, respectively.

Over the last month, investors pushed the stock market to extremely overbought, extended, and deviated levels. Currently, the deviation from the long-term bullish monthly moving average is at the most extreme since 1997. Furthermore, the stock market is now highly overbought, which has typically preceded more significant market corrections.

For nearly 5 decades, the NFIB Small Business Cost of Labor index has been a good barometer, especially for extended cycles. Based on this gauge, it took 19 months (on average) for the US economy to be in recession once the reading >=8.

FYI: The most recent reading is 12... (needless to say this is an all-time high and this index has never failed).

The path out of the pandemic continues to defy straight-line forecasts. The hope was that getting the virus under control by vaccinating a large percentage of the population would turbocharge an economic recovery. Now we know it’s not that simple. As the chart below shows, countries with pre-pandemic challenges haven’t escaped them.

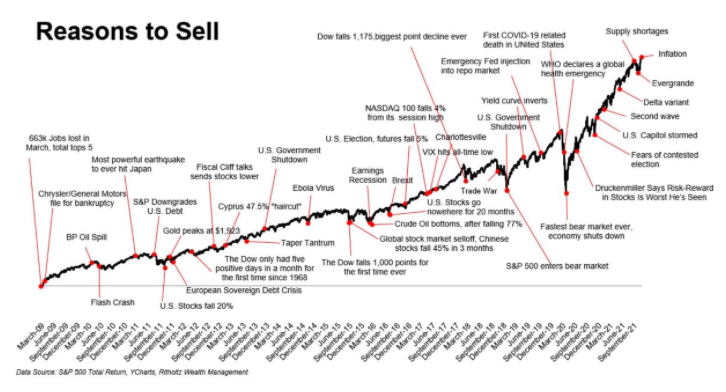

Focus on what you can control. There are always reasons to sell.

Time horizon is everything.

Logos LP October 2021 Performance

October 2021 Return: 5.14%

2021 YTD (October) Return: 17.97%

Trailing Twelve Month Return: 56.43%

Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) since inception March 26, 2014: 25.04%

Thought of the Month

“The function of the margin of safety is, in essence, that of rendering unnecessary an accurate estimate of the future." -Benjamin Graham

Articles and Ideas of Interest

The best market indicator over the last 34 years. Interesting article by Ralph Wakerly which looks at six major market indicators and their track record in navigating the last seven bull/bear market cycles. Investment advisor sentiment has the best track record. CAPE has little value as a short-term timing tool, but is powerful in forecasting future long-term market returns. CAPE is currently near historical highs, signaling weak returns over the next ten years. Technical analysis is controversial and murky. Contrary to many academic studies and proponents of efficient markets, some technical indicators have proven useful. But their effectiveness varies with time. And most technicians don’t rely on any single indicator.

Generation lockdown: Where youth unemployment has surged. Young people around the world have found themselves shut out of the labor market—and the consequences could linger for years to come. Niall O’Higgins, one of the authors of the ILO report, warns of the consequences of being shut out of the labor market for an extended time. “Clearly there is a serious danger that young people being out of work for a long period is likely to damage both the individual’s earnings prospects and the society’s productivity and long-term earnings potential.” The damaging effects go beyond economics. In countries with relatively young populations, having a large number of out-of-work youth can contribute to criminality and political instability.

There's a massive chasm between government policy and our energy reality. Eric Nuttall suggests that it is epically frustrating that in Canada, a country blessed with some of the most abundant energy resources in the world, the majority of the population suffers from profound energy ignorance: the lack of knowledge of how hydrocarbons are used, how critical they are to our daily lives, and the realistic timeline to replace them with a “renewable” alternative. Without oil and natural gas, we would literally be back in the Stone Age, experiencing a fraction of our current standard of living. So how did we get here, where the average Canadian thinks the end of oil is at hand, politicians contemplate the necessity of limiting production growth, and where we have lost sight of how blessed we are as a nation to be gifted with such valuable energy resources produced in one of the most ethically and cleanest manners anywhere in the world? Joe Oliver also reminds us that although Canada represents only 1.6 per cent of total emissions and cannot make a difference to global climate, we have a moral obligation to do our part in a worldwide effort. A common-sense approach would be to optimize our contribution while limiting damage to the economy. Instead, we seem determined to minimize our effectiveness and maximize self-harm.

America needs a new scientific revolution. A repurposed antidepressant might help treat COVID-19, a remarkable study found. The way this research was funded highlights a big problem-and bigger opportunity-in American science. The Atlantic diagnoses several paradoxes in the current U.S. system.

The bio revolution: innovations transforming economies, societies, and our lives. Mckinsey suggests that a confluence of advances in biological science and accelerating development of computing, automation, and artificial intelligence fueling a new wave of innovation. This Bio Revolution could have significant impact on economies and our lives, from health and agriculture to consumer goods, and energy and materials. We believe this is one of the best investment themes for the next decade. We like IONQ, KZIA, WST, CRL, RGEN, BDSX.

AI is no match for the quirks of human intelligence. We may sometimes behave like computers, but more often, we are creative, irrational, and not always too bright.

I’m a life coach, you’re a life coach: the rise of an unregulated industry. Fascinating piece in the Guardian charting the rapid rise of an unregulated industry at a time when the demand for mental health services is outpacing supply. Operating in the murky realm of “empowerment”, where personal development and financial success blur together, Life coaching Schools are having their moment yet are they empowering their largely female client base with the tools and support they need? Or selling them an unattainable fantasy?

No One Cares! Our fears about what other people think of us are overblown and rarely worth fretting over. Arthur C. Brooks for the Atlantic suggests that we are wired to care about what others think of us. As the Roman Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius observed almost 2,000 years ago, “We all love ourselves more than other people, but care more about their opinion than our own,” whether they are friends, strangers, or enemies. This tendency may be natural, but it can drive us around the bend if we let it. If we were perfectly logical beings, we would understand that our fears about what other people think are overblown and rarely worth fretting over. But many of us have been indulging this bad habit for as long as we can remember, so we need to take deliberate steps to change our minds.

The metaverse will mostly be for work. Stanford professor Jeremy Bailenson has been thinking about virtual reality and the metaverse for decades. As of 2020, he even teaches in it (more on that in a moment). For all of the chatter from Facebook/Meta, Nvidia, and other companies about building the metaverse, though, he thinks the metaverse will be mostly empty. That is to say, there won’t necessarily be a lot of things to do in this immersive version of the internet.

Unions are on the rise, but so are the robots. U.S. manufacturers hired 60,000 people in October, double economists’ estimates and the most since June of last year. It was a robust showing, led by automakers. But payrolls in the sector are still down by almost 300,000 since the end of 2019, even as many large industrial companies are reporting sales above pre-pandemic levels. Last month’s recruitment success will only make a modest dent in the nearly 900,000 open manufacturing positions as of the end of August. The tight labor market has created a moment for unions: Deere & Co. workers this week felt so confident in their value to the company that they voted down a revised contract proposal that included substantial wage increases and enhanced retirement benefits. It’s also creating a moment for robots.

Our best wishes for a month filled with joy and contentment,

Logos LP