"It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent." -Charlie Munger

On a recent trip abroad I took some time to think about the decision of 51.9% of UK voters to leave the European Union. As I sifted through the commentary regarding the historic vote, what struck me was how wrong the "experts" got it. The consensus of public opinion experts - at least if one uses prediction markets as a proxy - was that voters would in the end decide to stay in the EU. At certain points on Thursday before the results of the vote were released, the probability of a "remain" vote implied by betting odds stood at 90 percent. Furthermore, the majority of hedge fund managers worldwide looked at the stats and also concluded that the law of averages supported their decision to position for a "remain" vote to pass. Even the billionaire hedge fund manager Leon Cooperman told an audience of Wall Street insiders on Wednesday that there was a 70 percent probability that Britain would stay inside the European Union. "I don't worry about Brexit," he added. I myself as Head of Strategy at my investment firm Logos LP also made this mistake.

How could we all have been wrong? How could we "experts" have been caught flat footed in the face of an outcome the statistical averages so clearly suggested? The chapter on mathematics from one of my favorite books on investing by Robert Hagstrom suggests an answer: the concept of variances. Most people look at averages as basic reality, giving little consideration to the possible variances. Most of us have a tendency to see the world along the bell shape curve with two equal sides, where mean, median and mode are all the same value. The reality is that things are not so neat. Things do not always fit in a symmetrical distribution and instead skew asymmetrically to one side or another. What causes a distribution to skew to left or right is variation. As variation on one side or the other side of the median increases, the sides of the bell curve are stretched either right or left.

What does this mean in the context of Brexit? Without diving too deeply into the specific reasons 51.9% of UK voters choose to leave, many voters demonstrated high variance. Research has shown that in our "modern" digital age people make up their minds too late. According to a recent report by the market research firm Opinium, 20 percent to 30 percent of voters make a final decision within a week of casting their ballots, half of them on the day of the vote. This suggests that although a majority of UK voters polled to stay within the UK many politicians and experts ignored or simply downplayed the widespread attitude of disillusionment and misunderstanding amongst the electorate. This high variance pulled the curve to form a right skew.

In a right skewed distribution, the measures of central tendency do not coincide; the median lies to the right of the mode and the mean lies to the right of the median. If the experts had been more attuned to the concept of variance they would have been able to think deeply about the characteristics of those voters who populated the right skew of the distribution. Those individual voters who were so disillusioned with the status quo (remain in the EU) that they were unable to make up their minds until the last minute. Perhaps this knowledge would have changed their predictions.

Either way the above explanation leads me to believe that our culture favors a powerful bias to neglect or ignore variation. As the result of the Brexit vote demonstrates, focusing exclusively on measures of a central tendency can lead us to make significant mistakes.

Is there a lesson for investors? The answer is yes. As suggested by Hagstrom, perhaps the most important lesson for the prudent long-term investor is to grasp the differences between the trend of the system and the trends in the system.

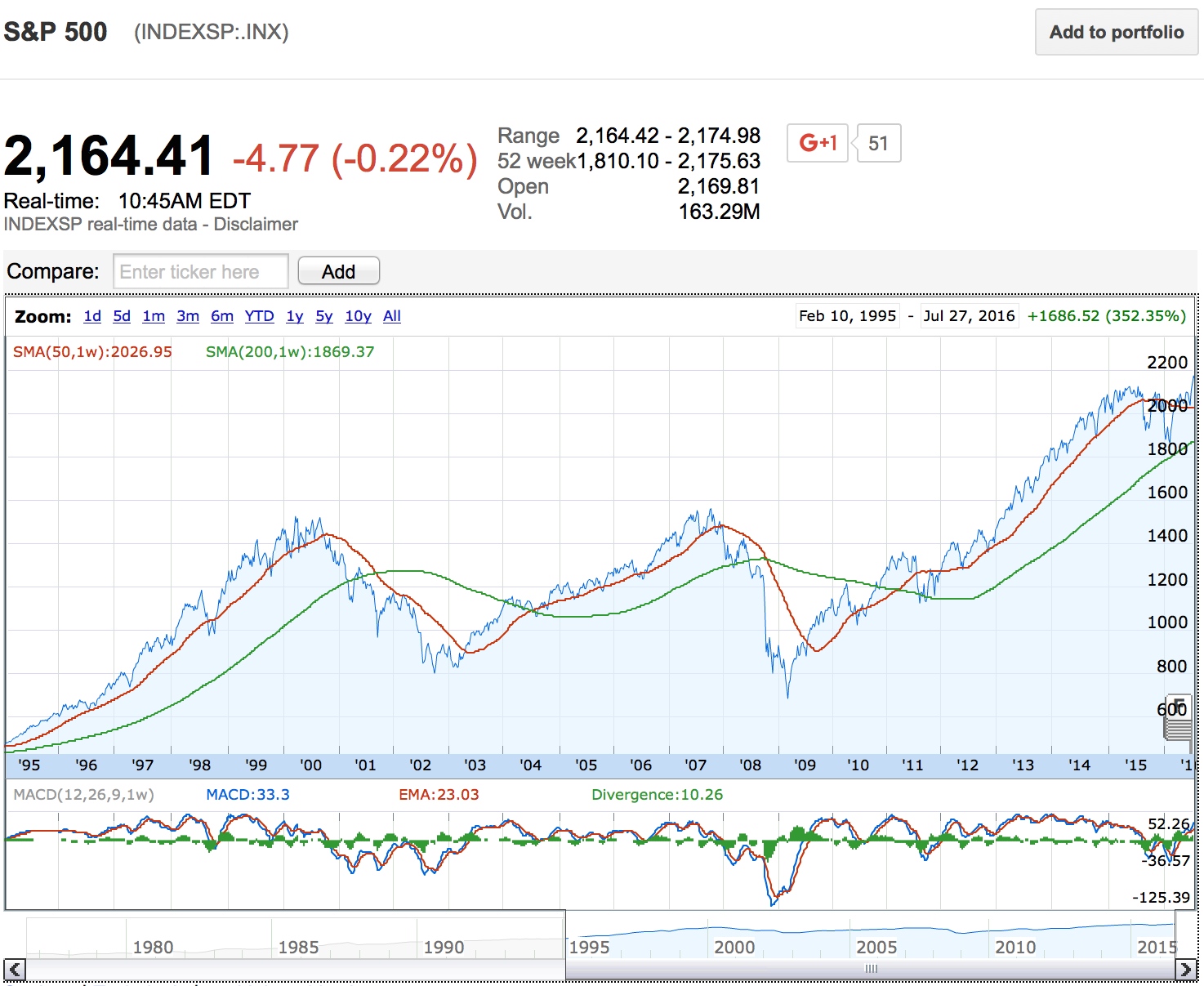

There is an important distinction to be made between the average return of the stock market and the performance variation of individual stocks. To illustrate the significance of this lesson one has only to consider periods in which the S&P 500 (NYSEARCA:SPY) has been stuck in a sideways pattern. Consider the following charts:

The above chart shows the S&P 500 from 1995 to present. Albeit a recent breakout which began July 1, 2016, note that from roughly December 5, 2014 the S&P 500 has gone sideways. Consider the following chart which provides a more recent snapshot:

For the vast majority of an investor's lifetime he or she will be exposed to either bull or bear markets which either go up or down. Yet at present, the investor appears to face a sideways market in which the major indexes remain range bound without a significant and sustained move higher or lower. Should investors thus conclude that stocks are a poor long-term investment?

Can history offer any insights? Consider one of the most pronounced sideways markets in history which occurred between 1975 and 1982. On October 1, 1975, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (NYSEARCA:DIA) stood at 784. Roughly 7 years later, on August 6, 1982, the Dow closed at the exact same 784. Fast forward to the present and with the market currently appearing to be stuck in a similar holding pattern, many forecasters and "experts" are concerned. They fear that in light of corporate earnings declines, weak global growth, unprecedented global monetary policy and investor complacency p/e multiples will fall leading to at worst a major correction or at best a prolonged period of low returns i.e. a sideways market.

It is no wonder that investor bearishness is at a record high. Based on research conducted by Bank of America investors ended June with the highest cash allocation on record at 5.7% on average and the lowest equity allocations in 4 years. Moreover, it looks as if investors are capitulating into bonds with an annualized year-to-date return from global government bonds at 25% in 2016, the highest return in 30 years. These three bearish indicators combined with the fact that inflows into precious metal funds hit a record during the first week of July, all point to the fact that investors are very bearish on global equities. Furthermore, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch's Bull & Bear Indicator, fell to an "extreme bear" reading of 1.6 on June 28. Is the "herd" right about the system? Should investors stay away from stocks?

In Hagstrom's book he points out that during the sideways market explained above which lasted from 1975 through 1982 Warren Buffett and Billy Ruane were both able to generate impressive returns. During this period in which the DOW gained exactly 0 percent, Buffett was able to generate a cumulative return of 676 percent and Ruane was able to generate 415 percent…

It would appear that the herd might be correct in their read about the trend of the system but dead wrong about the trends within the system. Diving deeper, Hagstrom found that over the 8-year period, only 3 percent of the 500 largest stocks on the market at that time went up in price by at least 100 percent in any one year. Yet over rolling 3 year periods, 18.6 percent of the stocks, on average, doubled. That equals 93 out of 500. But when the holding period was extended to 5 years, an average of 38 percent of the stocks went up 100 percent or more; that's 190 out of 500.

What a mistake it would have been to focus on the market average and avoid stocks altogether during this period. To have done so was to ignore the variation within the market and thus to miss out on the myriad of opportunities to generate excess returns by investing in high quality businesses.

Whether using averages to forecast the probable result of votes such as Brexit or perhaps the US presidential election or the future returns of the stock market we would do well to pay attention to the role variance plays as we distinguish between the trend of the system and the trends in the system. We may find that there is much more at stake than simply our ability to generate excess returns over the long term…

For original article published on SeekingAlpha click here.