Good Morning,

Stocks fell for a fifth straight day on Friday after the U.S. government released employment data that missed expectations by a large margin, adding to mounting concerns that the global economy may be slowing down.

The indexes posted their biggest weekly declines of the year. The major indexes all dropped more than 2 percent this week. The Nasdaq snapped a 10-week winning streak, while the Dow notched its second weekly decline of the year.

To put things in perspective, while the headline was that the S&P suffered its worst week in 2019, the index gave back 2.5% of the 19+% gain achieved during the recent rally.

The U.S. economy added just 20,000 jobs in last month, marking the weakest month of jobs creation since September 2017. Economists polled by Dow Jones expected a gain of 180,000.

The data come amid growing concerns about the global economy possibly slowing down. Data out of China showed its exports slumped 20.7 percent from a year earlier, far below analyst expectations and wiping out a surprise jump in January.

The weak data all come less than 24 hours after the European Central Bank slashed its growth forecasts for the euro zone and announced a new round of policy stimulus.

Our Take

The bears came out again this week screaming the usual platitudes they’ve been pushing since 2015: “The bull market is old and tired, the economic recovery has run its course, we are headed for a recession and the market’s best days are behind us.”

This may or may not be true, but it is important to remember that investors as humans have a tendency to think in terms of extremes. Things are “good” or they are “bad”. You should be “in” the market or “out” of the market. Given this tendency, it is no surprise that most pundits will offer an insight that suggests “go all in” or “get out”.

The reality is that much of the market’s activity occupies a middle ground. Things are fine and there is no need for any extreme actions or reactions. Why?

Because there are no immutable rules that explain what is going on in the market. There are no physical laws at work in investing. The future is uncertain, vague, and random. Psychology dominates and therefore there are no laws only tendencies.

As such, instead of thinking in extremes which imply the existence of laws governing the market such as “when the yield curve inverts that means a recession is coming thus get out of equities” it is better to examine certain tendencies which can be associated with the stock market.

What tendencies can we observe? Nick Maggiulli points to several:

1) Stocks will provide long-term positive returns

The historical evidence illustrates that equity markets around the globe have provided long-term positive returns to investors.

The equity market has been in a bull market:

76% of the time since 1929.

80% of the time since 1940.

84% of the time since 1980.

The majority of the time, stocks mostly go up.

2) Higher returns do not come without volatility

You can put your money in stocks and sleep tight....but the reality is far more punishing. Most developed country stock markets from 1900-2018 experienced at least one an annual decline of at least 37%. Furthermore, in a recent article in Bloomberg which backtested a “God” portfolio (an equal-weight portfolio comprising the best 100 stocks in the Russell 1000 since the bottom of the financial crisis that would have returned nearly 20 times the benchmark) to the bottom of 2009 and found that even this portfolio fell behind the benchmark by as much as 10 percent for part of certain years and also plummeted more than 22 percent at certain points -- six percentage points more than largest drawdown for the S&P 500.

"If God is omnipotent, could he create a long-term active investment strategy fund that was so good that he could never get fired?” The conclusion was no. While long-term returns were obviously astounding, shorter stretches -- the ones by which fund managers are often judged -- were “abysmal.”

Large crashes and volatility help explain why equities have a positive real long-term return. You are being compensated for taking risk. The compensation process simply requires patience.

3) Markets occasionally crash

Markets crash from time to time, but then they recover. Market crashes happen because of a rapid shift in investor psychology. Sometimes this shift is warranted but other times the market is oversold and a recovery becomes inevitable.

4) Cheap stocks and rising stocks tend to outperform the rest

Though stocks in aggregate tend to do well over the long run, cheap stocks (i.e. value) and rising stocks (i.e. momentum) tend to do even better. Although there is a lot of talk at present surrounding the relative “failure” of “classical” value strategies based on low price-to-book it is best to think of “value” as stocks trading at a discount to their intrinsic value.

Musings

This month we wish to highlight two pieces of news:

We see a unique opportunity in the markets at present. Please contact us for more information.

After receiving many requests, we have also decided to launch a 1 on 1 coaching service designed to help investors build their own custom equity portfolios. Please contact us for more information.

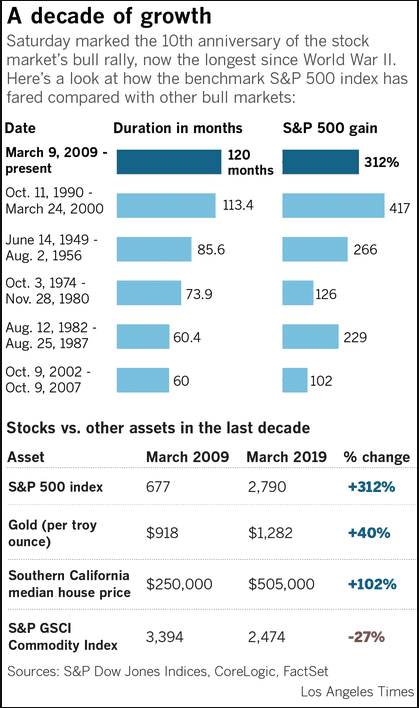

Charts of the Month

The majority of the time, stocks mostly go up more than pretty much everything else.

Logos LP February 2019 Performance

February 2019 Return: 3.03%

2019 YTD (February) Return: 8.41%

Trailing Twelve Month Return: -8.32%

CAGR since inception March 26, 2014: +13.46%

Thought of the Month

"There were a lot of questions today — people trying to figure out what the secret to life is, to a long and happy life: You don’t have a lot of envy. You don’t have a lot of resentment. You don’t overspend your income. You stay cheerful in spite of your troubles. You deal with reliable people. And you do what you’re supposed to do. And all these simple rules work so well to make your life better. And they’re so trite." - Charles Munger

Articles and Ideas of Interest

Why we fell for clean eating. The oh-so-Instagrammable food movement has been thoroughly debunked – but it shows no signs of going away. The Gaurdian suggests that the real question is why we were so desperate to believe it. In the spring of 2014, Jordan Younger noticed that her hair was falling out in clumps. “Not cool” was her reaction. At the time, Younger, 23, believed herself to be eating the healthiest of all possible diets. She was a “gluten-free, sugar-free, oil-free, grain-free, legume-free, plant-based raw vegan”. As The Blonde Vegan, Younger was a “wellness” blogger in New York City, one of thousands on Instagram (where she had 70,000 followers) rallying under the hashtag #eatclean. Although she had no qualifications as a nutritionist, Younger had sold more than 40,000 copies of her own $25, five-day “cleanse” programme – a formula for an all-raw, plant-based diet majoring on green juice. But the “clean” diet that Younger was selling as the route to health was making its creator sick. Sound familiar?

The servant economy. Ten years after Uber inaugurated a new era for Silicon Valley, the Atlantic checked back in on 105 on-demand businesses. The basic economics of moving human beings and stuff around the physical world at the touch of a button is not an obviously profitable enterprise (almost none of this 105 are profitable despite raising over 7.4 billion dollars). Looking at this incredible flurry of funding and activity, it’s worth asking: These companies have done so much—upended labor markets, changed industries, rewritten the definition of a job—and for what, exactly? An unkind summary, then, of the past half decade of the consumer internet: Venture capitalists have subsidized the creation of platforms for low-paying work that deliver on-demand servant services to rich people, while subjecting all parties to increased surveillance. These platforms may unlock new potentials within our cities and lives. They’ve definitely generated huge fortunes for a very small number of people. But mostly, they’ve served to make our lives marginally more convenient than they were before. Like so many other parts of the world tech has built, the societal trade-off, when fully calculated, seems as likely to fall in the red as in the black.

What would happen if Facebook were turned off? Imagine a world without Facebook. The Economist reviews comprehensive research which suggests that it might be a better place.

By the Numbers: Toronto Real Estate vs. The Stock Market. I often get questions which pit the supposedly fabulous returns which Toronto real estate has generated against stock market returns and this excellent research by Vestcap does a great job to demonstrate that Toronto home ownership produced a 5.7% compounded return while the TSX and S&P 500 each grew by 7.9% and 11.6%, respectively. I also get questions about investment in rental properties vs. investing in common stock and this article does an excellent job comparing the two. In general, rental property can be an attractive investment, but profitability is highly dependent on local conditions, global REITs offer compelling value that can replicate much of the returns you could achieve by investing in rentals and investors in favorable markets (cheap real estate) can leverage rentals for large returns.

The greatest investor you’ve never heard of: an optometrist who beat the odds to become a billionaire. Dr. Herbie, as he is known to friends, is a self-made billionaire worth $2.3 billion byForbes’ reckoning—not including the $100 million he has donated to Florida’s public universities. His fortune comes not from some flash of entrepreneurial brilliance or dogged devotion to career, but from a lifetime of prudent do-it-yourself buy-and-hold investing.

Where do disruptive ideas happen? Not on a big team. Innovations are more likely to arise from lone researchers or very small groups.

How AI will rewire us. For better and for worse, robots will alter humans’ capacity for altruism, love, and friendship. As machines are made to look and act like us and to insinuate themselves deeply into our lives, they may change how loving or friendly or kind we are—not just in our direct interactions with the machines in question, but in our interactions with one another. Meanwhile, China has banned 23m people from buying travel tickets as part of their “social credit” system. People accused of social offences blocked from booking flights and train journey.

Our best wishes for a fulfilling March,

Logos LP